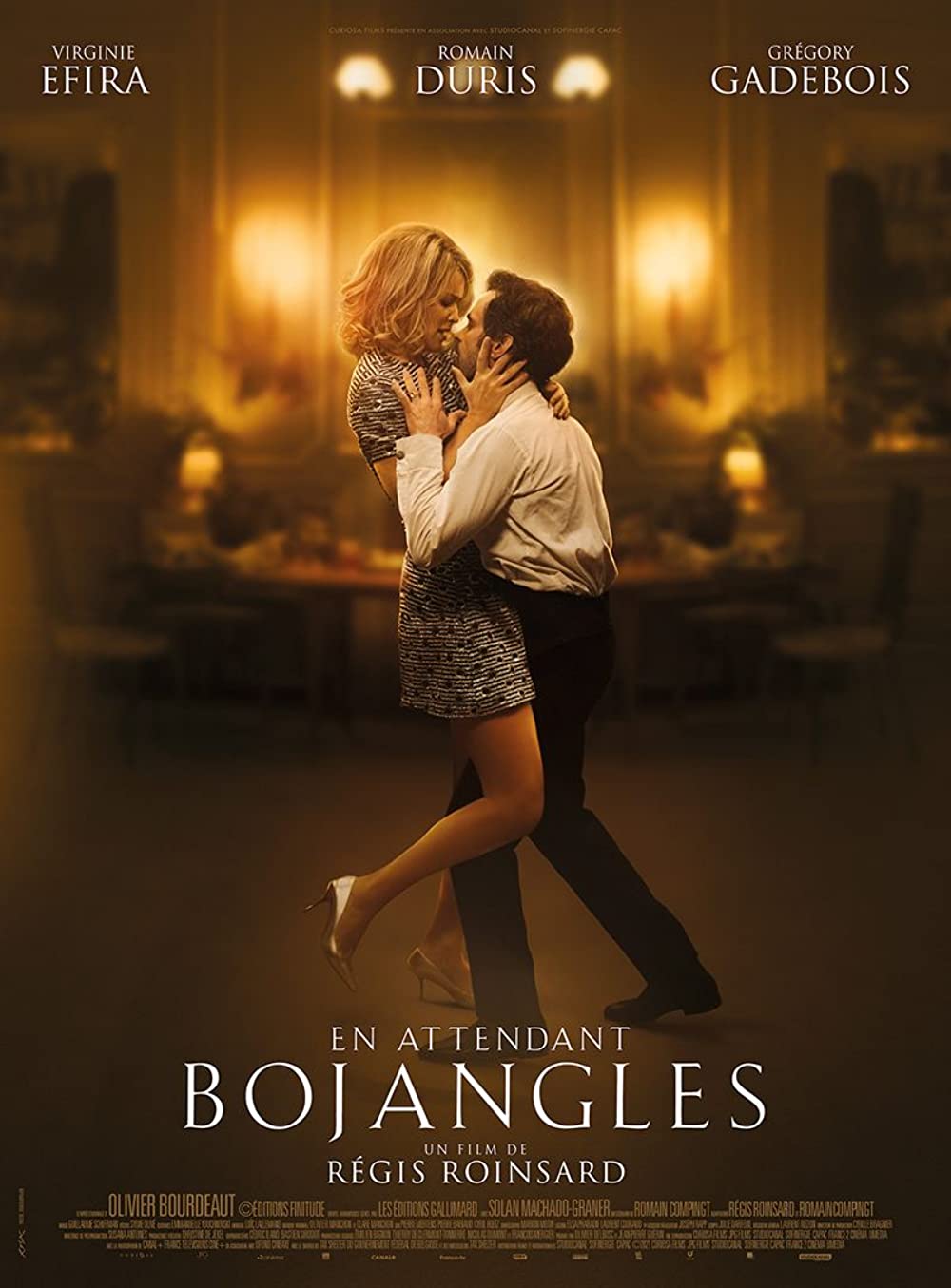

It’s not often that a French film comes along as moving as the romantic drama En Attendant Bojangles (2022), or “Waiting For Bojangles” in English, directed by Régis Roinsard.

As a longtime fan of French movies and 1960s culture, I couldn’t wait to see this film.

This film was adapted from the French best-selling novel of the same name, written by first-time author Olivier Bourdeaut, and released in 2016. The book was an instant hit with the French, and I saw it recommended on several occasions since I moved to France in 2019.

During my Christmas vacation this past December, I finally had the chance to read the book and quickly understood why so many people fell in love with the protagonists.

Set in Paris in 1967, En Attendant Bojangles tells the story of a French couple who personify the French joie de vivre and spend their lives telling stories, listening to music, reading books, dancing, and throwing fabulous parties for their friends.

Both Camille and Georges have wild imaginations, see sarcasm as a way of life, and regularly create extraordinary stories out of ordinary moments.

However, we quickly learn that the female protagonist Camille suffers from rapid mood swings, likely a mix of Emotional Dysregulation Disorder and Bipolar Disorder. This doesn’t stop her from living her life to the fullest – she wears fabulous clothing, dances elegantly, and reads voraciously.

“À côté d’elle, personne n’existe.”

– Georges

Camille’s insatiable appetite for life and overactive imagination are what draw Georges to fall in love with her immediately.

The family’s last name is even Fouquet. “Fou” is the French word for “crazy,” surely an intentional decision by the author.

As Camille’s mental battles slowly worsen, Georges tries to do everything in his power to keep the family together.

The magic of this film is that Roinsard succeeds at oscillating the audience between laughter and tears. He induces us to experience life just like Camille with a rapid swing of emotions from joy to sadness, and back and forth again.

If there’s one thing that French films do so well, it’s blurring fantasy with reality for an adult audience. En Attendant Bojangles is a film on par with other French fanciful films like Amélie (2001) and Jeux d’Enfants (2003) which excel in creating an unbelievable universe that the audience can’t help but immerse themselves in. These films teeter on the edge of reality and imagination, without going overboard, so one can easily fall off the precipice of believing that what’s happening on screen could, in fact, happen in real life.

En Attendant Bojangles takes viewers on a wild romantic adventure while tackling tough mental health issues. It shows us that sometimes, love means sacrifice. En Attendant Bojangles encourages the audience to imagine a beautiful story, even when life is sad.

“Quand la réalité est banale et triste, inventez-moi une belle histoire.”

– Camille

I highly recommend seeing this film if you have the chance. It will be screened in New York during the city’s French Cinema Week.

*Spoilers ahead*

Waiting for Bojangles Film Analysis

En Attendant Bojangles opens with a glamorous champagne-filled party on the French Riviera in 1958, where Georges and Camille first meet.

Georges tells far-fetched stories about his childhood that are patently false, yet he takes enormous pleasure in wowing his small audience of listeners. Camille dances in the middle of the crowd, seemingly aloof from the people around her.

When Georges asks what Camille’s name is, she sarcastically replies, “Jean-Paul, si ça vous chante” / “Jean-Paul, if that speaks to you,” while pretending to puff on a cigarette.

The moment is likely a reference to Jean-Paul Belmondo, a French New Wave film star of the mid-century, the time period when the film takes place.

Immediately, we see that Camille has an imagination like no other.

“Figurez-vous que…” / “Imagine if…”

– Camille

Costume Design

Camille’s first costume is a direct inspiration of one of American actress Grace Kelly’s outfits in Rear Window (1954) – a white tulle midi skirt with black feathers sewn near the waist and a black scoop-neck top. In every scene, Camille’s retro wardrobe is fabulously chosen by French costume designer Emmanuelle Youchnovski.

As Camille states during the opening scene, “Antoinette’s are always dressed well.”

After sharing their first dance on the banks of the Mediterranean Sea, Camille and Georges escape the party in a 1950s blue convertible car. They have a conversation in a French Riviera driving scene reminiscent of To Catch a Thief (1955) starring Cary Grant and Grace Kelly.

After crashing the car in front of the church, Georges and Camille decide to “get married” and say their own vows.

Instead of kissing Georges, Camille dodges his face and begins to cry as she hugs him. In this moment, we see the first sign of her emotional instability.

After the birth of their child Gary, the Fouquets take up residence in a beautiful Parisian apartment decorated in an eclectic mid-century style.

Set designer Sylvie Olivé skillfully takes us into the dreamlike world of the Fouquet home – baby blue walls, mismatched dining chairs, a giant chess board painted on the floor of the entryway, a stack of hundreds of unopened letters, and dozens of bottles of champagne and hard alcohol everywhere.

One of the most magically ethereal scenes is when we first enter the Fouquets’ home.

From the family bird Mademoiselle Superfétatoire flying over Gary and the chessboard in slow motion to Camille dancing in her living room, to Camille and Gary jumping on their sofa, also flying in the air with each leap, Roinsard uses several beautifully executed slow-motion shots to convey their surreal life.

The pair’s ecstatic happiness is exaggerated, but clearly intentional.

“Mon cavalier”

This is an endearing term for a date in French, and a nickname that Camille calls Georges quite often.

Imagination

“Quand la réalité est banale et triste, inventez-moi une belle histoire. Vous mentez si bien; ça serait dommage de nous en priver!”

– Camille

Camille regularly encourages her son to be creative and imaginative. She gets into a tiff with the school’s headmistress and explains that she reads to him la belle prose every evening to encourage his creativity.

Music & Dance

“Quand mes parents dansent, ils sont sur la lune. Ça fait trop haut pour avoir une discution.”

– Gary

Music and dance are significant themes of this film.

Marlon Williams covers the Nina Simone song the film’s title refers to with his own version of “Mr. Bojangles,” a song that is played multiple times during the film – on the car radio after the accidental crash and subsequent church “marriage,” as well as on the record player at the Fouquets’ apartment.

The Fouquets love to entertain.

Their house is filled with dozens of bottles of champagne and other hard liquors. They throw bashes late into the night, and the film’s party scene was clearly inspired by the party scene of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961).

The family bird, Mademoiselle Superfétatoire, looks down on the party guests while perched on an armoire the same way that Cat peers down on the Tiffany’s party from a high bookshelf ledge. Both Camille and Holly Golightly hold extra-long cigarette holders during the party.

My only criticism of this film is the final dance scene in Spain. While the scene is powerful, I would have liked to see Camille dance as the book describes. She simply stands in the middle of Georges and the Spanish guests who dance around her.

Nevertheless, the song “Adoro,” released in 1967 by Armando Manzanero, and reinterpreted by Lola Flores was the perfect choice to accompany this dance scene.

Cars

Cars – the American symbol of freedom during the 1950s – play an important role in the film.

From George’s impression of his life growing up in an American automobile factory, to his first drive with Camille along the Mediterranean coast, to his work as a car inspector at Garage de L’Essai, and finally as a means of escape to Spain after kidnapping Camille, cars symbolize the family’s need for escape.

French Expressions

The book and film make use of many French expressions in a way that only the French can truly appreciate.

The most prominent expression explains why the family takes off for Spain.

During one of their parties, Camille and Georges share that they dream of living in a chateau in Spain.

“Bâtir un château en Espagne,” literally “to build a castle in Spain,” is a French expression meaning to have unrealistic dreams or impractical projects, which apparently dates back to the 13th century. Yet in the film, Camille and Georges set out to literally do just that.

“On ne va pas s’empêcher de vivre à cause d’un proverbe!”

– Camille

Endearment

In one of her mental states, Camille decides to run an errand for the guests she believes are still in her home. She proceeds to leave the house completely naked except for stiletto heels.

A close family friend, L’Ordure, advises her to cover up so she doesn’t get cold, and Camille only puts on a white feather hat before continuing out the door, saying “You’re absolutely right! What would I do without you?”

L’Ordure and Gary watch from the window as Georges chases Camille across the street, tearing off his own clothes, before embracing her on the street – to the shock of the passersby.

It’s the film’s most endearing scene and shows just how far Georges is willing to go so Camille doesn’t feel out of place.

I loved this scene. It was my absolute favorite moment from the entire film!

3 comments

I have seen bad films in my life but this is probably the worst. To think that this pretentious, painfully long, vapid exercise in futility has been exported to the US is beyond me.

The poetic dance of words in the novel appears to be translated seamlessly into a visual spectacle on the screen. It’s heartening to see such attention to detail and dedication in bringing a beloved book to life. Your review has definitely sparked my curiosity, and now I can’t wait to experience the whimsical world of Bojangles!

Happy to read that! 🙂